Reading Time: 8 min 33 sec

Reality Is Broken1 by Jane MacGonigal is a splendid reflection on game design from a top-down perspective, introducing the craft more as a philosophical revelation than a psychological manipulation for players.

The book starts by identifying game as a form of work with four unique features: objective, rule, feedback and autonomy. The stem logic here is that people actually love work because of the significance, or purpose it imbues into them. However, work in reality is either too poorly designed, or limited in providing an ample amount of these four features to engage a participant.

McGonigal argues that even though game requires consistent effort just as real work does, it differs from work in all these features. As a matter of fact, game is often designed with opposite traits of a real-life activity, so that it could “fix” the disappointing reality and truly unlocks happiness through hard work. She proceeds further to list 7 prominent elements that enables a game to do that. I’m going to explain each of them in this post. I will also follow each case with some of my own observations and reflections.

This pretty much summarises the first half of Reality Is Broken. The latter half of it switches from concepts to implementations, especially focusing on a specific game genre known as Alternate Reality Games, i.e. ARGs. Many case studies are conducted and discussed in this part. Since this post is mostly intended to illustrate the conceptual framework proposed, I’m gonna skip them for now. We might come back to the cases in another post discussing ARGs in the future.

With the outline told, let’s explore how game is actually the work that fixes all works! We are gonna review the 4 features of work in this post, and discuss the 7 traits that enhance them in the next one. I will also add in my own takes on the author’s conclusion in the end.

4 Features

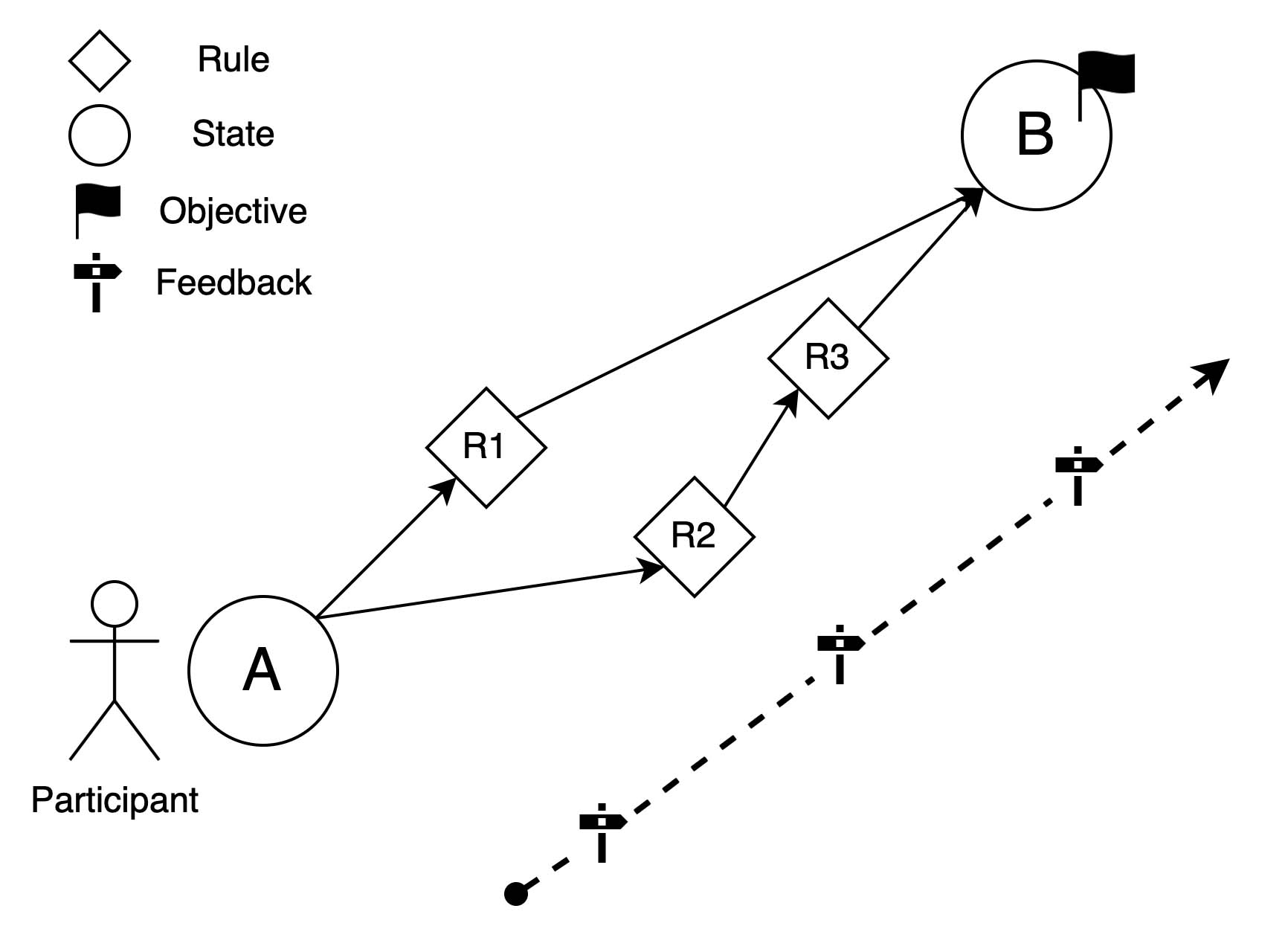

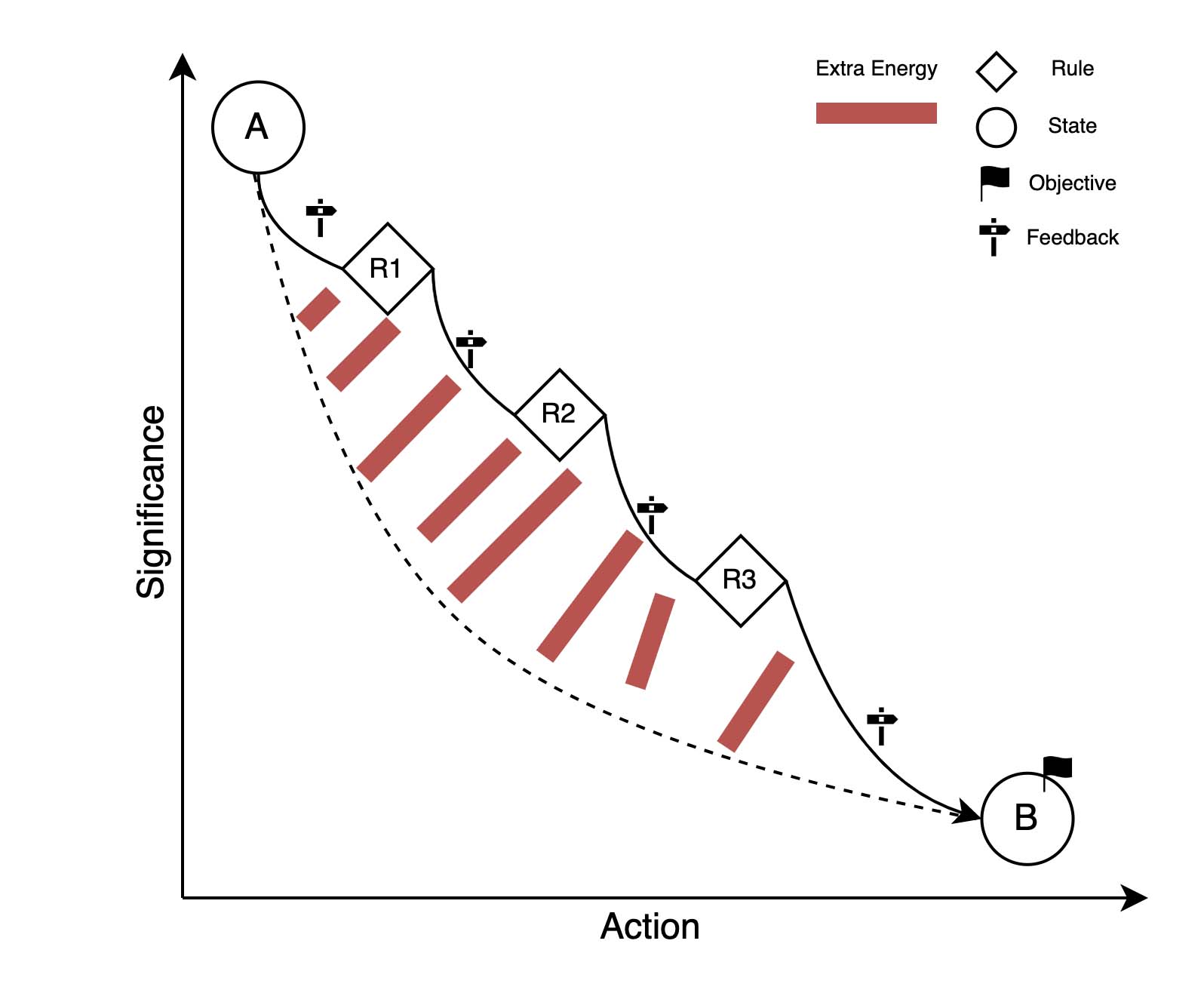

A work has 4 core features that make it work (sorry, last pun💦). We can define them quickly here. Let’s assume a work process is going from A state to B state with effort in a system:

- Objective(Identity): Where is B?

- Rule(Variety): How to go from A to B?

- Feedback: How much longer till B?

- Autonomy: At A, a participant always wants to go to B.

According to the frequently quoted Job Characteristics Model2, a fifth term should be added, which is Significance, i.e. how going from A to B changes other participants’ behaviours. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume we are in a single-agent system and ignore it for now.

With a cross reference table drawn on these 4 features, we can easily see how game differs from reality work:

| Objective | Rule | Feedback | Autonomy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reality | Fuzzy, often changing. | Hard to understand, with conflicting instructions. | Weak, often none at all in short term. | Few choices, passive failure. |

| Game | Accurate, fixed. | Easily understood, often with no instructions. | Realtime, significant feedback. | Ample choices, positive failure. |

Apparently reality work scores poorly on all 4 features. Game, therefore, is an essential work supplement to help people find happiness. The key point to take away here is that people don’t hate work: to the opposite, they love it and can’t live without one. Work in reality, however, is just too far from its ideal state to make people engaged.

Game/Work Dynamics

This is where my opinion differs from the author’s: instead of examining each feature separately, we should analyse them under a single system, with a single ruling quantity. We will call this quantity “game energy”. I will introduce the idea first, and then explain my rationales for devising such an analysis framework.

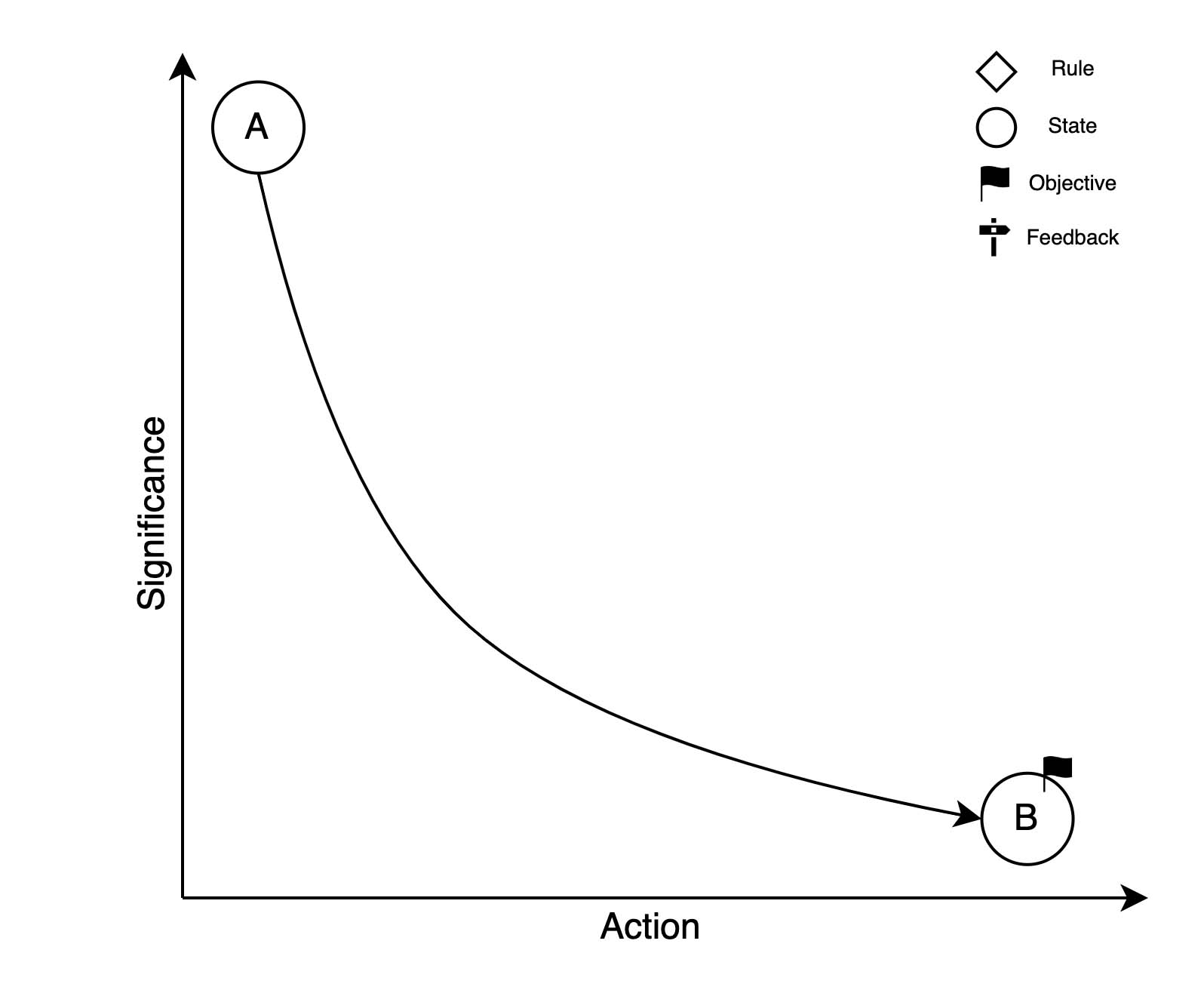

The intuition behind game energy is closely related to dynamics: the work process above can be easily illustrated with an analogy to a dynamical system that decays in total energy. Let’s assume potential to be a player’s feeling of significance, and momentum as a player’s extent of action. We will call them significance and action for simplicity. Some conclusions from the book can be translated into dynamic elements immediately:

Player won’t act without feeling autonomy, which comes from assuming significance.

Potential energy (significance) could be converted into kinetic energy (action).

The more a player acts, the less significance he will have, since the work/game has less challenge to offer. Upon reaching the final objective, both significance and actions are depleted.

Total energy decays over time.

The opposite of play is not work, but depression.

Having no objective to act on depletes significance, thereby leaving a person in the stasis of boredom.

Substituting potential with significance and kinetic with action, we can then formalise our system assuming a Hamiltonian system:

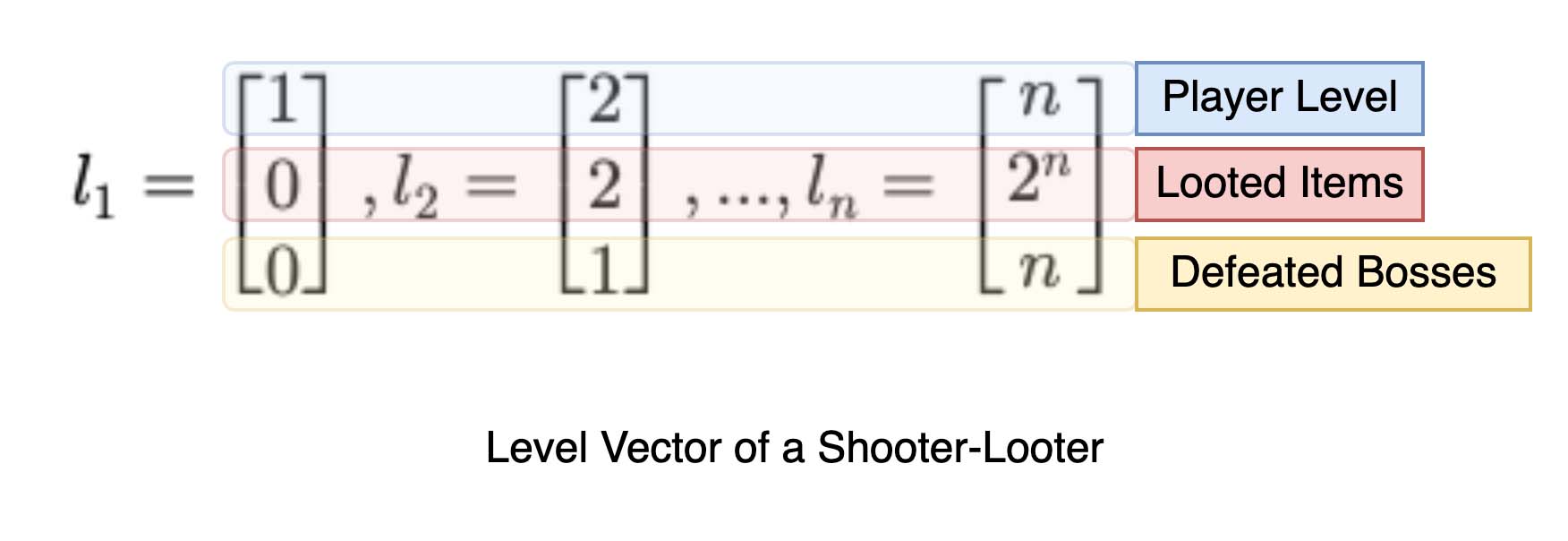

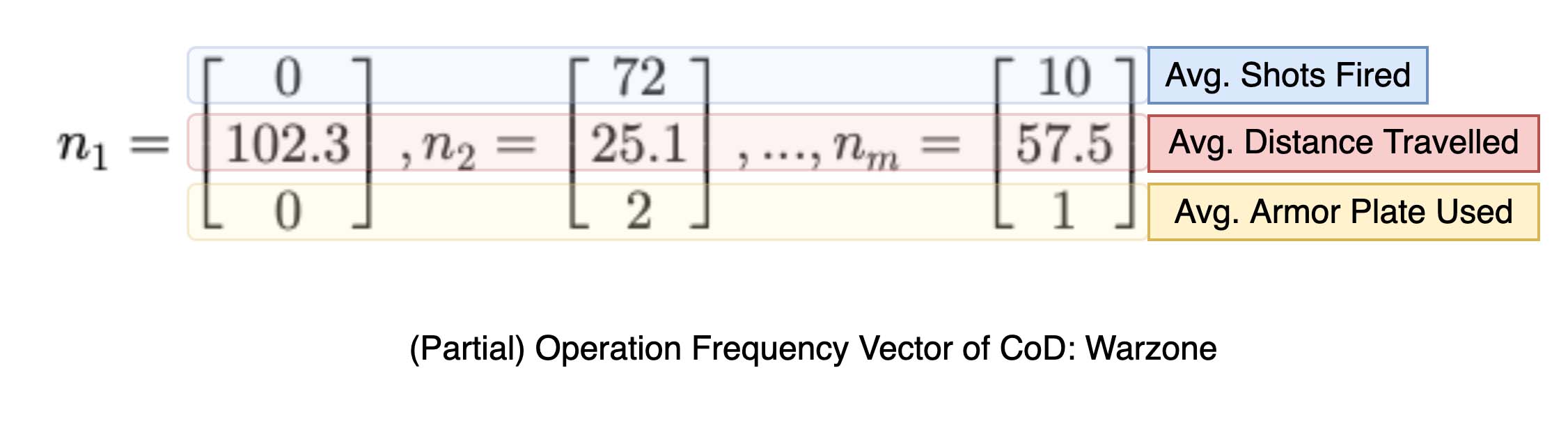

\[\begin{gathered}E\left( q,p\right) =S\left( l\right) +A\left( n\right) =E_{0}e^{-\lambda t}\\ \\ where\\ \\ E\leftarrow Game\ Energy,\\ S\leftarrow Significance,\\ A\leftarrow Action,\\ l\leftarrow level,\\ n\leftarrow operation\ frequency,\\ E_{0}\leftarrow Initial\ Game\ Energy,\\ \lambda \leftarrow decay\ constant.\end{gathered}\]The game energy decays over time to zero (we assume an arbitrary exponential decay here). The level vector dictates significance. The operation frequency vector dictates action. Note that time t only affects game energy, but not significance or action. This indicates that we are “converting” time into progression in levels and operations. A game/work’s completion doesn’t necessarily require a fixed time constraint but has its own progression rules, and this is often the case in reality.

The level vector could be either discrete or continuous. It serves as the “progression” descriptor of a work, i.e. how much has been done. It could simply be time t in the continuous case, since many games, like Fruit Ninja, depends only on t to progress. In the discrete case, it might be attributed to artificial level sequences, such as Super Mario. Each of the dimension in a level vector represents a specific progression descriptor if there are multiple dimensions required to finish a work, e.g. planting bomb and killing enemies in CS:GO.

The level vector could be either discrete or continuous. It serves as the “progression” descriptor of a work, i.e. how much has been done. It could simply be time t in the continuous case, since many games, like Fruit Ninja, depends only on t to progress. In the discrete case, it might be attributed to artificial level sequences, such as Super Mario. Each of the dimension in a level vector represents a specific progression descriptor if there are multiple dimensions required to finish a work, e.g. planting bomb and killing enemies in CS:GO.

The operation frequency vector (OF vector) records how many operations a player is registering on average. It directly reflects the extent of a player’s action. In StarCraft, this could be a single-dimensional vector of a player’s keystroke per minute (APM3). This can also take a multi-dimensional form according to a more specific action categorisation. For instance, in Dark Souls, we have evasion, defence, attack and restoration. Operation frequency is generally discrete because of sampling, but could be continuous in special cases where consistent input is required, e.g. vehicle maneuvers in Forza Horizon.

The operation frequency vector (OF vector) records how many operations a player is registering on average. It directly reflects the extent of a player’s action. In StarCraft, this could be a single-dimensional vector of a player’s keystroke per minute (APM3). This can also take a multi-dimensional form according to a more specific action categorisation. For instance, in Dark Souls, we have evasion, defence, attack and restoration. Operation frequency is generally discrete because of sampling, but could be continuous in special cases where consistent input is required, e.g. vehicle maneuvers in Forza Horizon.

Let’s examine the four features in our new system now:

Without gamification, the state change from A to B follows the digram above. If we integrate over the curve, we will get the game energy E.

Without gamification, the state change from A to B follows the digram above. If we integrate over the curve, we will get the game energy E.

With gamification, we will be adding rules and feedbacks. They serve the following purposes confirmed by Reality Is Broken’s researches:

- Rules make work more challenging, so that getting from A to B requires the extra miles. However, explicitly stated rules make work challenging and interesting enough to engage a participant — it provides directions for figuring out how to achieve the objective.

- Feedbacks keep reminding a participant that he/she is heading closer to the final objective. They make sure that autonomy is always maintained during the work process.

We could fathom how adding a rule or feedback mechanism would change our significance-action graph now.

A rule requires extra energy to follow, so it must increase the area under the curve.

A feedback pushes the participant towards action by constantly reminding how much progress is left. Therefore, it will pinch the curve downwards.

Let’s draw the resulted graph:

It can be observed that rules need extra energy devoted into the system, which means a player needs to contribute more than just sitting there and watching a movie. Feedbacks, on the other hand, steep the curve downward between rules, s.t. the gamified work is not too windy/requiring to accomplish.

It can be observed that rules need extra energy devoted into the system, which means a player needs to contribute more than just sitting there and watching a movie. Feedbacks, on the other hand, steep the curve downward between rules, s.t. the gamified work is not too windy/requiring to accomplish.

We have successfully formalised all the observations from McGonigal into our dynamical system of work.

Rationales for Deriving Game Dynamics

What I cannot create, I do not understand.

Yes, it begins with the good old Feynman quote. Trying to come up with a single theory/system that explains how game works is a first step towards designing one in my opinion.

We have been immersed in so many theories from psychology, behavioural science and human-computer interaction in game design. They are all very valid knowledge, often experimentally-proven. However, why people enjoy game remains a mystery. See the discrepancy here yet? We have the notion of game but can’t explain it clearly even though it’s a fundamental human trait. When we approach a game project today, we can rely on nothing but the “many-to-one” approach: view it either as a software, behaviour or experience, jumping from perspectives and drawing conclusions.

There is nothing wrong with this approach. However, it shows that we do not fully understand game in the best case. We understand many other things relatively better than game: if you drop a ball, it will fall, that’s gravity. If you vibrate air in a certain frequency, you can hear a specific sound, that’s musical note. These theories, no matter how simple or complex, could all be expressed compactly and experimented upon. We can’t do the same to game yet. We have some vague ideas on what disciplines it might be relevant to, and then try to stitch it up with patches. We cannot use game as a fundamental unit in shaping reality, while we can use mechanics and other knowledge to build great inventions. We cannot design a game with a “one-to-many” blueprint, a unified theory that gives birth to all games.

Therefore, if I do not understand game, I cannot create one.

I think Reality Is Broken is a fantastic read because of its effort on this matter: by rediscovering game as a single entity, work, it takes an interesting step towards understanding the mystery of game. Now that we have a sensible notion of what game is, can we describe how a game acts? That’s where I think game dynamics could be a potentially useful theory.

Once we have such a unified system of describing game mechanisms, there are many interesting things we can try:

- Apply machine learning on game design pipelines. For instance, representation space of a game’s level design could be learned in the form of a level vector, which we have just introduced.

- Strategically reserve game energy and spend it. Instead of thinking in terms of fixed game features and spreading a player’s energy evenly among them, we could focus on crafting the most engaging game elements.

- Offer a truly quantitative, differentiable way of generating player reactions. They can now be back-propagated to the most basic game components for improvement.

- Offer a truly personal gaming experience. A realtime game dynamic simulation could offer each player the exact actions, rules and progressions needed.

- Rediscover serious gaming by truly examining the participant’s work content and improving it. These are just a few things we can tinker with, equipped with a system capable of describing game dynamics.

Conclusion

This is the first of the few posts that I intend to share regarding game dynamics, gently introduced from a book review. By itself, this post is also the first part of my entire review on Reality Is Broken.

In the next post on game dynamics, I will try to formally establish all the elements of the framework.

In the next post on Reality Is Broken’s review, we will cover the 7 traits found by the author which further explains people’s need of game.

Thanks for reading.

-

J. McGonigal, Reality is broken: why games make us better and how they can change the world. New York: Penguin Press, 2011. ↩

-

J. R. Hackman, “Work redesign and motivation.,” Professional Psychology, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 445–455, 1980, doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.11.3.445. ↩

-

“Actions per minute,” StarCraft Wiki. https://starcraft.fandom.com/wiki/Actions_per_minute (accessed Dec. 05, 2021). ↩

Comments